Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c.70-80 BCE - after 15 BCE), commonly known as Vitruvius, was a roman architect and engineer and he also studied Greek philosophy and science. He is one of our few written sources on Classical Greek houses, but even he is writing 400 years later, as a Roman not a Greek, so we have to be cautious about what he says. In his treatise called De Architectura/On Architecture he writes on the requirements of an architect, materials, styles, sites and planning, especially of houses, construction of pavements, roads, mosaic floors, vaults, decoration, hydraulic engineering, water supply, aqueducts, astronomy and war machines . So he covers a very wide spectrum of information, such that after its rediscovery in the 15th century CE it was still influential enough to be studied by architects to the recent times.

The treatise is split into ten books and the one we are interested in is Book 6 chapter 7 ‘On Greek Mansions’ and it’s interesting to see what he made of the Greek houses and how they compare to the archaeology we have from Olynthus.

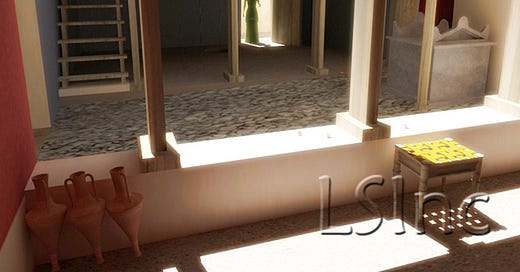

The archaeology confirms what Vitruvius tells us, that once you’ve entered the house ‘you then enter the peristyle’ which has ‘colonnades on three sides’, on the side which faces south are two piers with beams across them, the recessed space behind is ‘called prostas, pastas by others’. He moves onto the great hall, which I suggest was the courtyard space where ‘the ladies sit with the spinning women’. Archaeology evidence from Olynthus has raised the point that loom weights have been found in areas of the courtyard, the conclusion being that looms and spinning tasks were done around the courtyard. This makes sense as it’s the place where the sunlight would help the ladies see more clearly their tasks.

Vitruvius then goes on to tell us that either side of the recesses - the prostas/pastas there are bedchambers, again the archaeology at Olynthus gives us rooms in these areas, archaeology cannot say that are bedrooms as the artefacts left behind don’t help us be this specific (he calls these bedrooms the thalamaus and amphithalamus.) We move onto the rooms around the colonnades, which Vitruvius tells us are ‘the ordinary dining-rooms, the bedrooms and servants quarters’. Again the evidence of rooms are confirmed by the archaeology at Olynthus, he tells us that this part of the building is called ‘the women’s quarter, gynaeconitis’.

It seems logical to me that the women should have an area of the house for their use, they have the servants, the babies and children to manage, which the men generally would have little to do with, I thought of it a little like the modern nursery or the family wing of a house when I first read it. The women were the household managers who oversaw the day to day running of the house, keeping an eye on the servants (and to keep the male and female servants apart to reduce unwanted mouths to feed) and having space to feed and clean babies makes perfect sense. Vitruvius doesn’t tell us they are isolated or kept apart - just that they have their own space.

He carries on to tell us about another block of rooms next to these and although the layout of the Olynthus houses doesn’t show it as a separate block, Vitruvius is writing 300+ years later so houses could have got bigger and have a more elaborate plan. These rooms are for show, they have areas finished with ‘ceilings of stucco, plaster and fine wood panelling’. Sadly the archaeology cannot give us the ceilings, but we do have evidence of wall plaster and we do have floor mosaics in some rooms. These are the ‘halls men’s banquets are held’ - translated as the famous symposiums. These were the men only drinking affairs held in rooms we know are specific for this purpose, as the floors excavated at Olynthus and other sites has evidence of areas marked off for the couches which are placed around the walls, also the door is almost always off centre to give more space for another couch. Vitruvius tells us that these rooms ‘are situated with their own entrances, dining rooms and bedrooms, so that guests on their arrival may be received into the guest-houses and not in the peristyles’.

Why is this last point important?

Because the courtyard-house design was created to protect the women of the household and enhance the status of the husband. The way the entrance to the main house is only a single door going into a space that leads into the courtyard, that the rooms rooms off the courtyard are not visible from the doorway and the separate men’s drinking entrance are all designed to give women a space to ‘hide’ from the men. I use ‘hide’ very cautiously (mainly, I’ll be quite honest, because I cannot find a better word!) because this was not about controlling women and locking them away, it was about ensuring there was never ever any doubt that the children were the children of the husband.

One of the most important things for an ancient Greek man was his heritage and ancestry. To have a wife seen popping in and out of the symposium with more wine (the servants did that), greeting any man that came to the door, or being seen walking into her bedroom, did nothing but invite gossip and speculation.

The 21st century and the 5th century BCE are very different on a whole load of levels, but on one they are similar, the rumour mill in a small town is a vicious and nasty thing. One wrong word, one wrong action, can label a woman a whore or a ‘loose women’ (to use an old fashioned phrase) and by labelling a women this, you throw doubt on the legitimacy of her children. And her children are also her husbands children, so therefore the children’s paternity could be called into doubt, and in this a whole can of future worms could be opened.

We have the evidence to show us that women did go out and about on their own or with a servant, but it was in the pursuit of a legitimate task or job and it was in full sight of everyone.

The courtyard house was a revolution of a quiet societal movement. It’s design reflected a change in philosophy of how the Classical man thought of themselves. The idea that the house was the man’s ‘castle’ meant he had autonomy somewhere in his life and its possible he may not have had this freedom before. I might be going too far by saying this house design was a political movement but by saying this you get what I mean in the concept of ‘big’ ideas.

The courtyard house reflected the image the man wanted society to see. He had complete and utter control over his house and it’s contents, which is why the internal layout, as stated above, was so important for his reputation. He was also telling his polis that he shared their moral codes, and by sharing them he could then be a part of the new ‘corporate’ state where power to run the polis was shared amongst a body of, nominally at least, equal citizens.

Sources:

All quotes of Vitruvius comes from the Loeb Classical Library publication, translated by Frank Granger, Vitruvius on Architecture, Books 6-10, pp. 45-49, first published 1934.